The Ideal Female Form

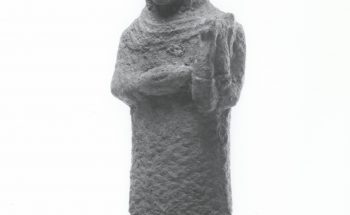

Plaster cast of a Roman copy of Praxiteles’s Aphrodite of Knidos. Original marble statue circa 350s BCE, plaster cast circa 1905. 21-109.

This piece is a plaster cast of a Roman copy of a cult statue of Aphrodite. The Greek sculptor Praxiteles carved the marble original for the city of Knidos in the fourth century BCE. The cast depicts the goddess of love, known to the ancient Greeks as Aphrodite and to the ancient Romans as Venus. The goddess stands in the nude with her right hand held in front of her pelvis and her left grabbing a cloth that drapes over a pot. The body of the Knidian Aphrodite was extensively reproduced in the Roman world. In the second century CE, funerary statues of individual women depicted in the guise of Venus: the goddess’s sublime body typically joins individualized heads of Roman matrons. The women so portrayed were literally shown as the present-day embodiment of the peerless goddess of love. The idealization of the facial features in this work suggests that we are looking at Venus rather than a mortal look-alike.

-Emily Profitt

- View the next object

- Return to the main page of the exhibit

- Or follow one of the links below to continue.